In each of the various exhibitions, everyday events and objects are associated with the memories and traumas of the artist’s biographical past. Moments of existential darkness, hybrid images intriguing in their seductive strangeness and visions of horror appear alongside poignant attempts to escape and cushion the blow, or the fall, of awakening. Dina Shenhav’s Tunnel, which is visible to all in the middle of the space and is made of a soft material, is a priori devoid of protective functions, and its material properties evoke not only an ability to insulate and seal and an intimate memory of a bed mattress, but also recalls the survival of the artist’s father in WWII; nightmarish creatures seek relief in the work of Holocaust survivor artist Osias Hofstätter; Dganit Ben Admon’s installation projects a fraught situation in which interior and exterior, and past and present, are in imminent danger of collapsing after a future earthquake – and seeks to mitigate it; Avi Sabah’s paintings pit the mundane against injustices, horrors, and nightmares from the time when did guard duty during military service – in a state between vigilance and fatigue, between dreaming and waking; Michael Liani’s exhibition presents an escape to the ultimate vacation in Eilat – so familiar to him from his youth – as moments of spectacular abundance, but also of a touching nightmare, in which escapism is an impossible escape option; and Penny Hes Yassour’s work is based on observations by laboratory researchers on the navigation of bats in the dark, thereby offering an experience of a mental map embedded in the body’s memory and senses, a non-hierarchical map based on personal experience and beliefs, in which fears set boundaries, and impulses draw nooks and crannies.

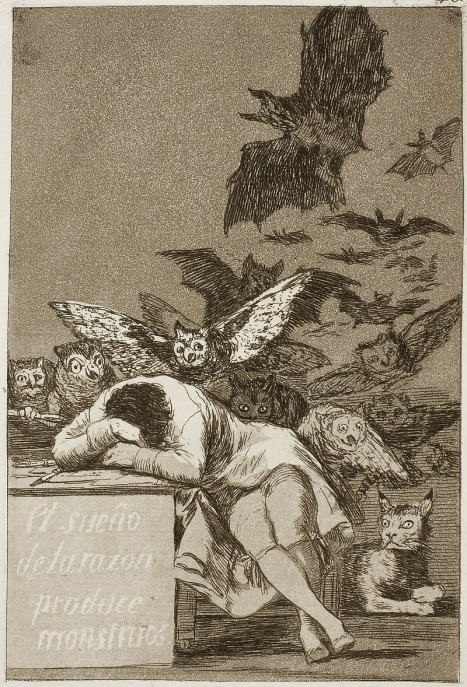

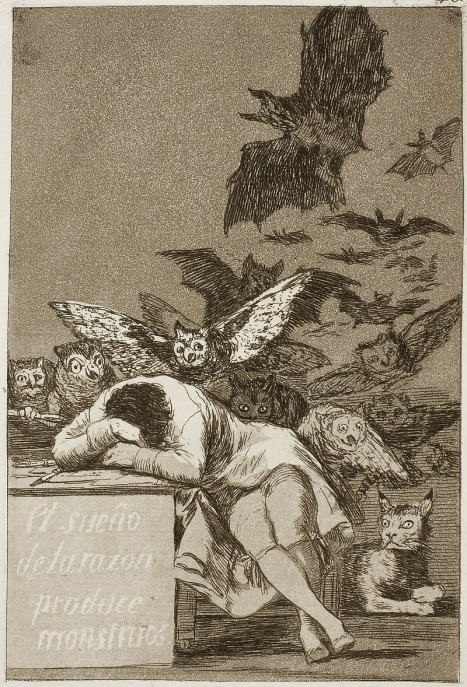

The exhibitions conjure up the famous aquatint by Francisco Goya (1746–1828), El sueño de la razón produce monstruos (The Sleep of Reason Produces Monsters) (Fig. 2), from the series Los Caprichos (1799), in which the artist is depicted sleeping, slumped over his work-table, and surrounding him and above him are terrifying nocturnal creatures, owls and bats. Thus the work of art is presented as a fraught space, oscillating between fantasy, nightmare, and angst, anchored in reality yet diverging from it. Interpretations of the image often refer to it as an expression of the artist’s tragedy-ridden biography, but focuses on its reading as a sharp social, cultural, and political critique of the failure of Enlightenment and reason in the face of the evils of the period. The grotesque creative realm that Goya depicted, like the critique he expressed back then, in late eighteenth-century Spain, seems more relevant than ever.

Fig. 1: Pesach Slabosky, This is the Third Dream I Remember, 2017, oil on canvas, 100x78x9 cm, courtesy of the artist’s estate and Givon Art Gallery, Tel Aviv

Fig. 2: Francisco Goya, The Sleep of Reason Produces Monsters, 1799, aquatint, from Los Caprichos, 21.2×15.1 cm

Less Reading...