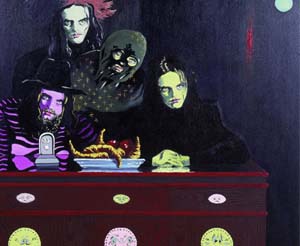

Roee Rosen | - Justin Frank, Retrospective (1900-1943)

Curator: Dalia Levin

Jan. 11, 2003 - March 22, 2003

The present exhibition-the first retrospective of the Jewish-Belgian Surrealist, held over half a century after her death-is an opportunity to shed some of the frustration reflected in Rosen’s failed effort to “observe” and “study” the artist. True: each question raised concerning Frank yields a few of contradictory answers, whether one queries her private life or her ethics and aesthetics. Because Frank was situated within several crucial junctures of Twentieth century culture, it appears we may learn a great deal from her life and work, yet at each such juncture she seemed to have done her best to antagonize, confuse and even repel those around her (and she seems to intimidate and confuse even today).