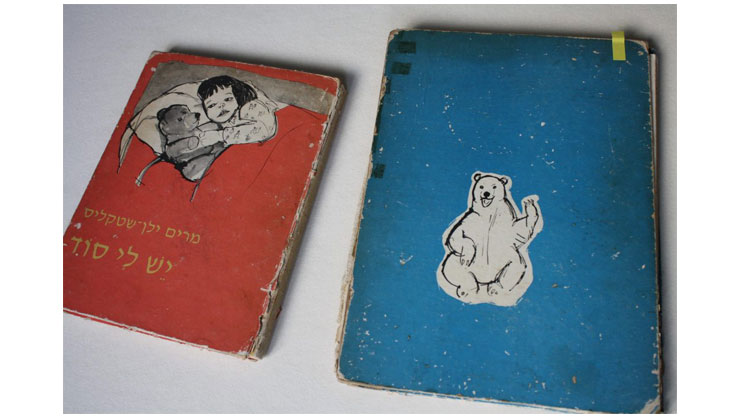

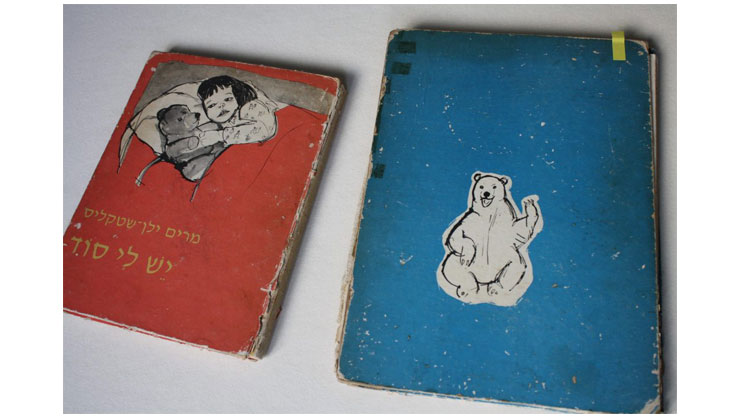

Just as Hayim Nahman Bialik’s poems for children have become identified with Nachum Gutman’s illustrations and Leah Goldberg’s writings are inseparable from Aryeh Navon’s, so is it almost impossible to make the distinction between the children’s literature written by Miriam Yalan-Stekelis, Fania Bergstein, or Nathan Alterman and Binder’s illustrations. From the mid-1940s to the 1970s she illustrated dozens of books, many of which are part of the classical corpus of Hebrew children’s literature. Binder’s drawings are easily recognizable: thin, black lines drawn quickly and pithily. At times, one or two additional colors were added to the black outline by the printer. Their style is a reflection of the spirit of the times in Israel, an ideological seismograph of simplicity and frugality that succeeds, despite economic and technical constraints, in expressing a deeply complex worldview. The childhood depicted by these images is multifaceted. On the one hand, it is informed by wonder, naivety, curiosity, dreaming and imagination, and the comfort of young family life surrounded by animals. However, at the same time, Binder creates a psychophysical image of pain, disappointment, sadness, false expectations and rumination. Thus, for instance, her illustrations depict an image of loneliness that is both melancholic and egocentric.2

To a large extent, Binder’s figure has remained enigmatic and forgotten. In this, one must say, she is unfortunately not different from many other women visual artists of her generation.3 Born to a family of book binders,4 Binder immigrated to Palestine from Poland in the early 1930s. Encouraged by her brother, the painter Abraham Binder, who had immigrated a few years before her, she devoted herself to artistic creation and became part of the cultural and artistic milieu of Tel Aviv. She illustrated books and plays, designed theater sets and costumes, and showed her work in museums and galleries around the country. For many years she and the poet Nathan Alterman had an affair, openly, which continued until his death in 1970. Binder left her estate to the Alterman Archive at the Kipp Center for Hebrew Literature and Culture, Tel Aviv University.

Moran Shoub wrote an original audio play based, among other materials, on personal correspondence between Binder and her poet lover. Performed in Hebrew by Chava Alberstein, Aya Lurie, Oded Menda-Levi, Zvi Salton, and Moran Shoub, the play is available on the museum’s audio guide. It complements the experience of this exhibition. The viewers are invited to linger, sit on a swing or on the steps, and get to know two artists whose lives are bound by books.

1 In this context one may recall the words of Walter Benjamin, who describes the material aspects of an old book from his school library as if it were a landscape: “Its pages bore traces of the fingers that had turned them. The bit of corded fabric that finished off the binding, and that stuck out above and below, was dirty. But it was the spine, above all, that had had things to endure – so much so, that the two halves of the cover slid out of place by themselves, and the edge of the volume formed ridges and terraces. Hanging on its pages, however, like Indian summer on the branches of the trees, were sometimes fragile threads of a net in which I had once become tangled when learning to read.” Walter Benjamin, Berlin Childhood around 1900, trans. Howard Eiland (Cambridge, Mass. And London: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2006), p. 59.

2 Ruth Gonen, “Visual Interpretations of Miriam Yalan-Stekelis’ Writings,” Iyunim besifrut yeladim, no. 12, 2002, pp. 39–60 (Hebrew).

3 See Ruth Markus (ed.), Women Artists in Israel, 1920–1970 (Tel Aviv: Hakibbutz Hameuchad, 2008) (Hebrew).

4 In German, Buchbinder means book binder – hence Tzila Binder’s last name.

Less Reading...