Most of her pieces are short, succinct and meticulous. They are screened in a loop, which enables repetitive viewing that unfolds, reveals and constructs the multiple layers of meaning contained within each and every one of them through the time cumulating in the course of the cyclical viewing.

Marshall’s works relate to reality, while expressing passions and fears, and without refraining from themes located in socially tabooed areas. While her two sons often appear in her works, the works are not biographical in essence. They touch upon fundamental moral and philosophical issues concerning culture, society and the individuals comprising it, while relating to ostensibly normative values of permissible/forbidden or worthy/unworthy, challenging the viewer’s aesthetic-moral boundaries.

The scenes revealed in the works are unsettling, at once terrible and beautiful; misleadingly oscillating between imagination and reality, immorality and innocence, they invoke disconcert and aversion as well as attraction and awe.

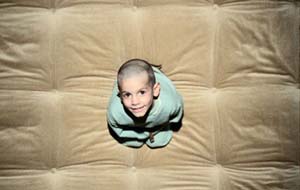

Don’t Let the T-Rex Get the Children begins with a partial close-up of the illuminated face of a young boy, looking with amazement at the camera. The camera pulls back from his face with a long, slow motion, exposing its full frame, lingering on his eyes and expression, which could be a smile, or some sort of uncontrolled or uninhibited emotional disintegration and unwinding.

The prolonged pullout gradually reveals the boy’s body, kneeling in a padded cell, wearing a green straitjacket. As the camera draws away, the cell’s depth is revealed, and the child’s mute laughter continues to be seen but not heard, the picture becomes uncontainably frightful.

The work’s title, alluding to the individual’s struggle against an external control mechanism – be it the medical, social, intellectual or emotional apparatus – is directed outward as an open cry that renders the viewer a partner in struggle or alternatively, a partner in crime.

Aeroplane presents a small crop-duster repeatedly crossing the screen, approaching and drawing away, ascending and nearly crashing, disappearing from the screen and promptly reappearing, while performing a set of obscure flight maneuvers. The white trail of smoke left behind accumulates into a cohesive form of one letter and another, until the word “KILL” is ultimately revealed on screen. Extending diagonally across the sky, it cuts the air in terms of its sharp statement, forthwith dissolving and disappearing into thin haze in terms of its materiality.

The revealed action is an odd display of strength that borrows its operation technique from various fields of discourse and practice, among them the agricultural, military, and national-ceremonial.

Playground features a simple, ascetic-looking church that seems to be rooted in the midst of a largely desolate landscape. Opposite the building, a young boy plays with a ball kicking it against the church wall, time and again. The ball-bounces against the wall are clearly heard, but the ball itself remains invisible. The church structure seems to shake and sway with each kick of the ball against its side, yet remains in place.

With much beauty and force, the work metaphorically describes the ongoing power struggle between various elements comprising the well-known social order: religion, sports, contemporary culture, tradition, youth, etc. It explores the link between these social, cultural and religious structures and the individual’s power to rebel, change, or accept them, thereby being admitted into their frame.

Hadas Maor

Exhibition Curator

All works Courtesy of Team Gallery, New York

Less Reading...