Thus, in one of the works from the series Princesses and Dragons – oil paintings executed, not unintentionally, on a wooden board, the prevalent surface for oil paintings until the late fifteenth century – she takes Paolo Uccello’s well-known painting, Saint George and the Dragon (ca. 1460, The National Gallery, London), casting herself in the role of the princess in the painting, while excluding Saint George from it. She doesn’t need a knight in shining armor to rush to her rescue; she can manage the dragon that has become a pet of sorts (albeit a somewhat irritable pet…) which she leads by a chain. Her confidence and control of the situation are emphasized by the pose in which she stages herself; while Uccello’s original princess is presented in profile, clearly helpless, looking in her savior’s direction, Galnoor is standing in three-quarters profile, possibly looking at the viewer, possibly shooting a reprimanding glance at the unconventional pet she has chosen for herself.

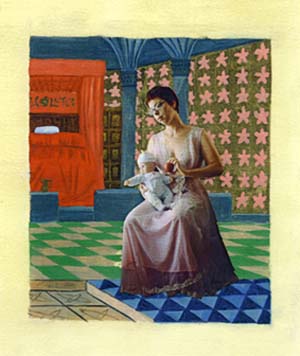

In the series Mary’s Life Cycle the artist casts herself in the role of Mary, mother of Christ. Being a prominent iconic female figure in the history of art, the choice of Mary is not surprising. In this series too, Galnoor creates a world dominated exclusively by women, and when other figures emerge in it apart from Mary, these are the artist’s friends. In this female world there is no room even for Joseph, Mary’s husband, who, like poor Saint George, was screened – perhaps for the first time in the history of art – out of the scene of the Flight into Egypt.

And perhaps, beyond the preoccupation with the issue of gender, the works embody an element of wish fulfillment. For who hasn’t dreamt of being a prince/princess, gaining fame by vanquishing a fearsome dragon (or any other heroic deed), and acquiring the same “respectability” enjoyed by figures that are still considered icons in Western culture.

Less Reading...