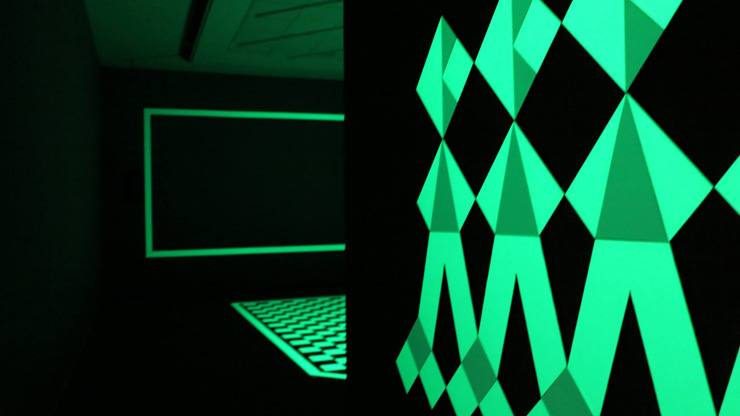

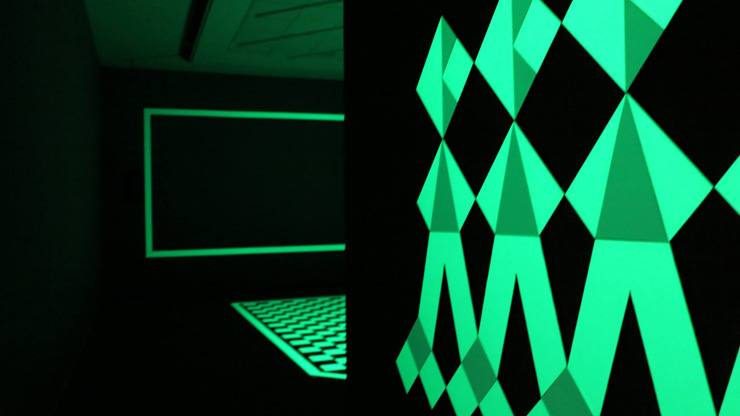

The installation shifts between blinding light and total darkness, with the photoluminous material used as an orientation anchor, creating a kind of mental space outside reality and time. Safe and Sound (Version II) is inspired by Berlin’s rave and nightclub scene that evolved from subculture to mainstream, as well as the first decades of the 20th century, when Berlin was famous for its night life and hundreds of dancehalls, ballrooms and cabarets. Jazz, foxtrot and swing were played to enthusiastic audiences who danced the nights away. When the Nazis rose to power, this sort of leisure culture was considered “decadent”. The party officially declared these dances to be a corrupt pastime for the Aryan nation, and imposed severe restrictions on public dancing. As a result, Berlin’s ballrooms, cabarets and nightclubs were abandoned for many years. In the postwar decades, the city’s nightlife was slow to recover, and the nightclubbing culture flourished again only in the 1990s, after the fall of the Berlin Wall. Techno music created a new reality in which both time and old hierarchies were broken up. As described by Théo Lessour in his book Berlin Sampler, techno was a music that reveled in the present moment and pushed current events to the sidelines, that rejoiced in entering into a continuum where everything was equal and worth experiencing, where no one thing was better than any other.[1]

Rodeh’s work also blends the present with the past – in her own words, “I wish to blend the sounds of today’s club culture together with the aesthetic roots of the ballroom culture of the first half of the 20th century”. Traditionally, dancehalls represented an implicit form of cultural-political protest both in the darkest eras of German society, when it gradually adopted the Nazi ideology, and in the period after the fall of the Berlin Wall, when youngsters felt a need to consign the gloom and severity of the Communist regime to oblivion. Rodeh’s work is layered with the multiple verbal connotations of the title Safe and Sound, as well as with the turbulent history of Berlin’s clubs throughout the city’s history.

The use of photoluminous safety material highlights the tension between liberating and regimented security. The protected club space, removed from everyday life, enables clubbers to experience a sense of security, disinhibition and free expression, but the photoluminous material also symbolizes a supervised freedom and a controlled environment.

Rodeh’s work manifests the “return to Berlin” as a return to a place as well as a journey back in time. Thus, she obliquely and tacitly evokes the memories of the dark historical events which took place in-between the dancing eras, events which spelled the demise of the city’s wild nightlife back then, and in a different way, led to their current revival.

Light programming: Shahar Bareket

[1] Théo Lessour, 2009. Berlin Sampler: From Cabaret

to Techno: 1904-2012, a Century of Berlin Music, p. 307.

Berlin: Ollendorff Verl

Less Reading...